In Mexico, ‘Roma’ Lit a Fire for Workers’ Rights

A role in Alfonso Cuarón’s film showed me how art can provide a voice for the disenfranchised.

By Yalitza AparicioMay 23, 2020

This essay is part of The Big Ideas, a special section of The Times’s philosophy series, The Stone, in which more than a dozen artists, writers and thinkers answer the question, “Why does art matter?” The entire series can be found here.

I never thought that a movie alone could prompt social awareness and change. But when the director Alfonso Cuarón released his film “Roma” in 2018, with me in the lead role, that’s exactly what happened. Suddenly people in my home country of Mexico were talking about issues that have long been taboo here — racism, discrimination toward Indigenous communities and especially the rights of domestic workers, a group that has been historically disenfranchised in Mexican society.

In fact, it was my involvement in this film that led me to better appreciate the importance of art.

Art sheds light on the urgent, necessary and at times painful issues that are not always easy to approach because we as a society have not been able to figure them out. Art lays bare our brutal reality — a reality that is complex, diverse and often unfair — but it also presents us with the amazing opportunity to give voice to the unheard, and visibility to the unseen.

Four years ago, when a casting call for “Roma” was issued in my city, Tlaxiaco, in the state of Oaxaca, in southern Mexico, I almost didn’t go to the audition. The film industry was alien to me. As a child, I couldn’t relate to the people I saw on movie screens; the actors and actresses were nothing like the people I knew, and their stories centered on worlds far away from my own. As an adult, I studied to be a teacher, and had no thoughts of becoming an actress.

Fortunately, I did answer the call, and things changed very quickly for me. I was cast in the role of Cleo in “Roma,” and eventually was able to bring to screens around the world a character who represented people who had gone unseen: Mixtec women who worked as maids.

The movie intimately recounts the day-to-day life of a middle-class family in 1970s Mexico City. At that time, Mexico was experiencing political and social upheaval. National turmoil brought to the fore problems that still persist to this day, namely the normalization of classism, racism and denigration, along with other forms of segregation and belittlement based on skin color, ethnicity, sexual orientation or social class.

Although discrimination is not often spoken about in Mexico, it is a very real problem. According to a 2017 poll conducted by Mexico’s national office of statistics, 65 percent of Mexicans think that few to none of the rights of our Indigenous communities are respected.

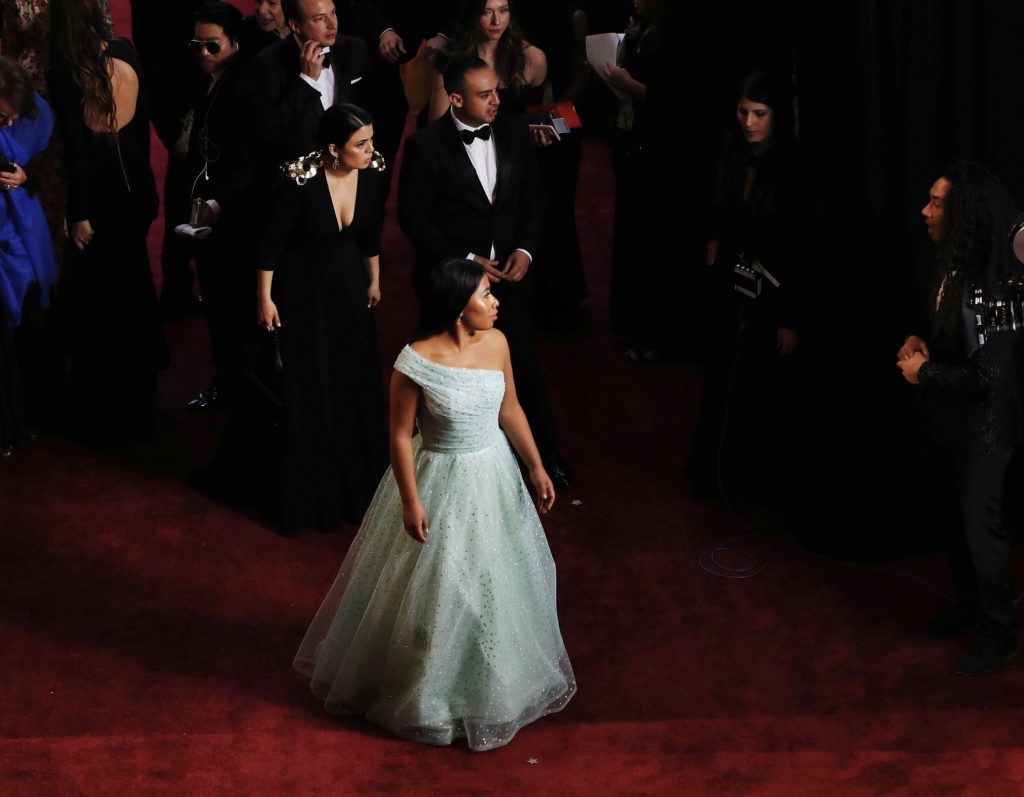

I have firsthand experience with this kind of discrimination. After I was nominated for an Academy Award for portraying Cleo, racist comments began to circulate on social media. Commenters questioned why I was nominated, making references to my social and ethnic background. An Indigenous woman was not a worthy representative of the country, some said. It was hard for me to see and hear these sorts of statements. But real conversations were happening because of them. Eventually, these discussions highlighted the cultural and political importance of diversity in society, art and the media.

In the movie, two Indigenous women, Nancy Garcia and I, even spoke Mixtec, one of the 68 languages currently spoken in Mexico, aside from Spanish. Nancy is a speaker and advocate of this beautiful language, a language that she has been teaching me, a clear example of the cultural plurality in Latin America that we don’t often see reflected in cinema.

By vividly showing the discrimination that disproportionally affects Indigenous people, “Roma” also sparked a collective cultural awareness that paved the way for a momentous legal victory in Mexico.

On May 14, 2019, a few months after the Oscars ceremony, in which “Roma” won three awards, Mexico’s Congress unanimously approved a bill granting the two million domestic workers in the country rights to social protections and a written employment contract, along with law-mandated benefits such as paid vacation days, Christmas bonuses and days off.

The impact of this victory reached far beyond Mexico’s borders: The National Domestic Workers Alliance in the United States wrote an open letter dedicated to the women in the movie and summoned support for a National Domestic Workers Bill of Rights being considered in the American Congress.

Cleo had a very profound effect on my life, and playing her placed me on my current path: I am using my newly discovered activism to improve social conditions in Mexico, champion gender equality and promote diversity wherever I can. In short, I’m trying to build a better world — one in which we aren’t judged by our appearance or typecast for certain roles, and where we aren’t limited by what we see, read or hear.

As a child growing up in Oaxaca, the lack of representation in the film industry communicated negative messages. Today, I’m turning that around. When we do not see people who look like us in the media, we should not be discouraged. Rather, we should stand up and demand representation and not let others criticize our culture or dismiss our concerns.

The role of Cleo, and filmmaking in general, have provided a showcase for many people to be heard, seen and valued. This is a first step toward making the rest of society aware of the importance of joining in the fight to create a world that is more diverse and inclusive.

This — nothing more, nothing less — is the importance of art.

Yalitza Aparicio is an actress and, since 2019, has been a UNESCO good will ambassador for Indigenous peoples.

Now in print: “Modern Ethics in 77 Arguments,” and “The Stone Reader: Modern Philosophy in 133 Arguments,” with essays from the series, edited by Peter Catapano and Simon Critchley, published by Liveright Books.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.

Fuente: nytimes.com